A horse can drink 35 – litres of water each day, but the actual amount required is determined by a number of factors including the duration and intensity of exercise; the weather, temperature, and humidity; the horse’s fitness, body condition, ability to sweat, and hari coat; and the amount and nature of the diet. Horses generally sweat to regulate body temperature, but in hot and humid conditions, sweat no longer evaporates, and it becomes an inefficient method of cooling. Heat produced by metabolism and exercising muscle exceeds the capacity for dissipation through evaporation, and it accumulates, increasing core body temperature, sometimes dangerously. Horses develop clinical signs of heat stress and even life-threatening heat stroke.

As evaporative cooling from the skin fails, core body temperature increases. In early stages, when temperature is only slighty elevated (just over 39.5ºC), horses will appear lethargic, lack impulsion, and you might have to encourage them to maintain gait or speed. Muscle cell function is impaired and damage occurs. Respiratory rate increases to below off heat, just as in a panting dog, and they may take longer than normal to recover after exercise stops. Heart rates may be elevated, and recovery to resting heart rate will be delayed. In the early stages of heat stress, horses will fail to perform at their best, and their recovery will be prolonged.

If a mild heat-stress condition is allowed to progress and body temperature climbs to critical levels, above 40ºC, gut motility stops, and signs of colic become evident. Heart rate can exceed 100 beats per minute, and arrhythmias are common. Horses can become wobbly and collapse. This is obviously an emergency situation, and immediate veterinary attention is needed. Intravenous administration of fluid and electrolytes will be required, and there is no guarantee that the outcome will be positive. Preventing heat stress, or at least identifying and addressing the condition in its very early stages, is therefore, critical.

For horses stabled in hot, humid conditions or those in transport, one of the earliest signs that they are struggling to regulate their temperature is loss of appetite. As core temperature increases, peripheral vessels are dilated to help increase heat loss through the skin. You can often see vessels standing out on the neck and chest at these times. In order to maintain this peripheral blood pressure, fluid is drawn from the lumen of the gut into the blood stream, and vessels supplying the intestinal walls are constricted. Digestion slows and horses lose their appetite. When this occurs, it is vitally important that horses drink well to replace sweat losses and to replenish fluid volumes in the blood stream and gut lumen.

HORSE WORKING, TRAVELLING, OR STABLED IN HOT, HUMID CONDITIONS DON’T ALWAYS DRINK ENOUGH.

The two main things that stimulate thirst are a drop in blood volume and a rise in sodium concentration. Horses, though, lose quite a bit of electrolytes in their sweat, so as they lose fluid, they may also lose enough sodium to keep the concentration of sodium in their blood reasonably stable. Without the increase in sodium concentration, they don’t get a clear signal to drink. In addition, horses have a number of behavioural issues that may stop them from drinking. They can be particular about the flavour or temperature of water, and in some environments, horses may just be too excited or stressed to drink.

HOW TO PREVENT DEHYDRATION AND ELECTROLYTE IMBALANCE.

When horses are travelling and exercising, digesta in the GI tract provides an important reservoir for fluid and electrolytes. A single flake of soaked hay can hold as much as 4-5L of water, and grass is already 90% moisture, so both are worthwhile parts of the pre-travel or pre-endurance race diet. Providing oral electrolytes that help maintain normal sodium levels, before and after travel or exercise, will also be important. As electrolytes added to feed may reduce feed consumption, a paste might be a more reliable delivery method.

Electrolytes added to feed and water have been shown to potentially reduce intake, and the last thing you want to do is reduce water intake when horses are dehydrated. Always offer a bucket of plain, clean water in addition to any treated water provided, to ensure picky horses will at least have something they will be willing to drink. A small amount of blackstrap molasses can be mixed in to electrolyte-treated water for flavouring. (Add it until you get a weak-tea colour.) Many horses like the sweet molasses flavour, so you can use this trick anytime you want to encourage horses to drink larger amounts or just to camouflage the taste of different waters encountered when traveling. Once they are drinking and replacing electrolyte losses, they will generally go back to eating too.

You must be careful, though, not to introduce large concentrations of sodium chloride into the gut when horses are already hot and aren’t drinking. The osmotic draw from salt draws fluid back into the lumen of the gut, reducing fluid in the vasculature and further reducing heat dissipation through the skin. Provide slightly lower but safer doses of electrolytes along with clean, fresh water to encourage drinking.

Hay and grass, along with grains, provide some potassium, calcium, phosphorus, chloride, and magnesium, but sodium levels are generally too low for all but resting horses. In studies looking at electrolyte changes in standardbred racehorses, resting, training, and racing, results demonstrated significant changes in potassium levels and lesser changes in sodium levels. A syringe of Pro-Dosa BOOST contains potassium, sodium, and chloride in ratios that reflect those findings. The levels of electrolytes included in Pro-Dosa BOOST are appropriate for most types of horses in work and travelling, including thoroughbred racehorses and sport horses involved in most pursuits. Endurance horses, on the other hand, often have more significant changes in sodium, chloride, calcium, and magnesium levels than other equine athletes, owing to the extended period of time they are racing and the large amount of sweat produced. For this reason, it is a good idea to provide sodium chloride (table salt) to endurance horses at a rate of about 30 g or 2 tablespoons per loop, in addition to a syringe of Pro-Dosa BOOST, which already contains good doses of potassium, calcium, and magnesium.

Providing your horse with optimal nutritional support for exercise, travel, and competition is critical for the maintenance of normal appetite and thirst, in turn required to sustain hydration and replace electrolytes lost through sweat.

Pro-Dosa BOOST contains significant doses of nutrients that help to support normal appetite and thirst including the following;

*Electrolytes, including calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus, as well as sodium, potassium, and chloride. These macro-minerals help to maintain normal thirst, hydration and the electrolyte balance necessary for muscle cell, cardiac, and nerve function.

*B Vitamins, which are needed in balance with each other for normal energy production, red blood cell formation, nerve cell function, and appetite;

*22 Amino Acids, that help support thirst in the dehydrated horse as well as providing the building blocks for protein synthesis, involved in muscle recovery and growth; and

*Trace Elements, including Copper, Iron, Manganese, and Zinc, important for red blood cell formation and general metabolism.

The body needs a full complement of nutrients in careful balance to achieve optimum health, performance and recovery.

Giving your horse one tube of Pro-Dosa BOOST at least two hours before loading them on the float will help them arrive at your destination in the best possible condition and ready for the competition ahead. Give an additional tube each day of competition, and for endurance horses, give a full tube between each loop, along with an additional tablespoon of ordinary table salt when it is hot and humid. Remember to sponge or hose hot horses with cool water, scraping them frequently until they have cooled, and keep them in the shade. Encourage them to drink by keeping them relaxed and providing fresh and tasty water. Feed soaked hay or grass, when possible, to provide extra water and electrolyte reserves.

THINK ALL “BOOST” PASTES ARE THE SAME? THINK AGAIN!

Download the PDF Article Here Think Again

The composition and balance of nutrients included as well as the safety and quality of each product is different, so buyer beware!

Recently, we have noticed a number of copy-cat “boost” products appearing in the marketplace. Some have chosen the same colours and package appearance or promotional text, and all have chosen a similar name and appear to have copied part of our formulation (the less expensive parts, anyway). None of these products have included the complete formulation contained in a Pro-Dosa BOOST, but they think you will be fooled by an only partially complete product that looks and sounds similar and sells at a lower price. I think, horsemen should think about why someone would do that.

It is said that the sincerest form of flattery is imitation. It does appear that some of our new competitors have recognised Pro-Dosa BOOST is of exceptional quality and composition, and they can’t compete with that. Instead, they hope to be mistaken for the same thing at a lower price. Since I didn’t make Pro-Dosa BOOST to be a cheap product with a large profit margin, I know they can’t make a similar quality product, any less expensive. They have to make a less-complete, poorer-quality supplement instead. While I suppose I should be flattered, instead, I am concerned about how many horsemen will think they are feeding my product, when they’ve bought a “copy-cat” by mistake. How many horses will be fed supplements that aren’t complete, balanced, or safe enough? How many people, feeding a copy-cat they think is ours, will think our product isn’t as good as it used to be when they don’t get the observable effects they have been accustomed to when feeding the original, tried and tested, Pro-Dosa BOOST, established in 2001?

WHAT DO YOU NEED TO REMEMBER ABOUT PRO-DOSA BOOST?

In order to achieve optimal metabolism, performance, recovery, and health, it is necessary to provide a broad spectrum of nutrients, in bioavailable forms, in ideal balance with each other and with the cofactors necessary for their absorption and function. The doses provided must reflect the requirements of horses under stress due to travel, hard work, racing, competition, and illness, as the administration of only some of the nutrients required or feeding quantities below or above requirements may result in imbalances that actually impair absorption and function. With this in mind, I developed Pro-Dosa BOOST to provide complete, balanced, and bioavailable nutritional support.

Because I made Pro-Dosa BOOST for the stables I had worked for in my veterinary practice, for years, I didn’t make it with profit margins or easy marketing in mind. I made it to make a difference to my patients and to make things easier and less expensive for my clients, who were my friends and not just face-less consumers, I didn’t know. I looked up the nutrient requirements published by NRC, and then I looked up other nutrition research and texts to fill in requirements not available through NRC. I compared those to what I had been providing for my patients in injectable form, and I referred to veterinary pharmacology texts and talked to exercise physiologists. I came up with a profile and doses of nutrients that, I believed, would be the most scientific and practical for competitive horses in my veterinary practice. I didn’t worry about whether or not horsemen would immediately understand the formulation or recognise the importance of some of the less familiar sounding nutrients. I focused on making a difference to equine health and welfare.

As a veterinarian, my clients trust me to provide safe, secure, efficacious, and ethical treatments for my patients. Product quality, therefore, had to be of paramount importance. I decided to make Pro-Dosa BOOST out of human food or pharmaceutical grade nutrients that would meet much higher purity standards than animal feed grade nutrients.

I thought it was important to measure the concentration of nutrients in the final product, because I wanted to be confident that I would be providing my patients the correct doses of each nutrient, not more or less, for best effect, and for their health and safety. If insufficient doses are given, then no impact or a negative impact on the overall health of horses may result. If you are buying a supplement that doesn’t contain what the label says, then at best, it’s a waste of money. At worst, it could be detrimental to your horses’ health. At the same time, giving too much of some nutrients is dangerous. Many horsemen will recall the tragic story from a few years ago about the group of polo ponies who died as a result of eating a feed supplement that contained ten times the amount of selenium that it was meant to, when an error was made in production of the product. I wanted to make sure that would never happen to a horse fed Pro-Dosa BOOST.

Finally, I wanted to be certain that I would not inadvertently cause harm though contaminants. I made my production and product tracking procedures as safe as possible by registering my facility in the NZ government inspected and certified GMP program. I used hazard analysis principles (HACCP) in developing methods of raw materials procurement, manufacturing, and finished product quality and safety assurance. I decided to submit all finished product for analysis for naturally occurring prohibited substances that may contaminate feed grade nutritional products and cause positive drug tests, and I submit all finished product for microbial culture to ensure it is sterile. Finally, I validated (proved) that my processes were consistently effective in producing a quality, sterile, and safe product that horsemen could feel confident and secure feeding to their horses. I wanted them to know that they could trust Pro-Dosa BOOST to be providing exactly what they were paying for and what their horses actually need to perform and recover at their best.

Think about what you are spending your money on and learn to read labels critically. Read my series of blog articles on “Reading Labels”, and please do contact me if you’d like help with general nutrition or comparing supplements and feeds.

Could Pro-Dosa BOOST produce a positive test? This question was asked of us frequently by trainers and horse owners, a few years ago. At the time, Pro-Dosa BOOST only had 1 mg of cobalt per tube, so the short answer was, “no, it wouldn’t produce a positive test”. We were asked the question many times though, and we felt there were likely many, many more horsemen who had the same concerns but who did not contact us to ask. We decided we had better take action to try to get some information out there for the wider horse community to see.

Cobalt has become a very significant issue in racing and other sports over the past few years. Following positive tests in Australia, racing authorities have made cautionary statements about the administration of cobalt to horses, and it has been reasonably well publicised that administering it at levels that result in the excretion of more than 100-200 micrograms of cobalt per litre of urine (depending on the racing jurisdiction) will result in a positive test. What hasn’t been explained is how much cobalt you can safely feed before those levels are reached. Racing jurisdictions have been working towards finding that threshold but have not yet released any information.

On a more basic level, horsemen and veterinarians have been provided with very limited information about the impact of “normal” levels of cobalt in the feed on the cobalt levels in urine. “Normal” levels may be significantly less than the threshold doses that will eventually be established. Instead, regulatory authorities have said that cobalt deficiencies are not common in horses, and they have recommended that it should be eliminated, as much as possible, from the equine diet until data is published indicating the maximum amount that can be fed.

What is cobalt and how much do horses require? Cobalt is a trace element needed by horses in very small amounts to facilitate normal physiology and metabolism. It is naturally present in feed stuffs, but as levels may be quite low, it is generally included in the formulation of prepared feeds and supplements.

The National Research Council (NRC) pre-2011, recommended daily dietary requirement is at least 0.1mg of cobalt per kilogram of dry matter intake per day. Your average 500kg racehorse can be expected to eat 2% of their body weight per day, which would be 10kg of feed on a dry matter basis. 10kg dry matter intake X 0.1mg cobalt required per kg dry matter = 1mg of cobalt required per day for normal health. According to NRC, resting horses require about half of that. NRC 2011 standards list reduced minimum requirements, ranging from 0.5mg to 0.6mg, depending on age and level of work.

In virtually all cases, feed companies use NRC guidelines when developing formulations, so most complete feeds will contain at least 1mg of cobalt per day, when fed as directed. A horse’s cobalt needs, therefore, should be readily met by its basic feed intake, as long as the cofactors needed for absorption and function are present in the diet. As horses in training for competition and racing are generally fed a well-balanced diet, most will be receiving the cobalt needed for normal health.

After completing a cobalt clearance study in Standardbred horses in training, in New Zealand, we concluded that we could remove cobalt from our formulation while feeling confident that Pro-Dosa BOOST would still provide complete and balanced nutritional support for optimal performance, recovery, and health. We wanted to ensure that trainers and horse owners, from all disciplines, could incorporate Pro-Dosa BOOST in their training regime, without any concern about producing a positive test for cobalt.

If you would like to read more about our findings, please follow the link to our cobalt clearance study.

With the rules of racing or competition quite variable from place to place and changing all the time, it is very important to consider the specific regulations that apply to you, in your sport, and in your part of the world before feeding Pro-Dosa BOOST according to label directions. If you are not allowed to “administer” anything on the day of racing or competition, consider the other ways and times you might be able to incorporate Pro-Dosa BOOST in your management system to ensure your horses are at their best when training, competing, and travelling.

- Feed Pro-Dosa BOOST rather than applying it to your horse’s tongue.

Pro-Dosa BOOST is comprised of a broad range of highly purified nutrients, in good balance with each other, and in quantities that reflect the increased requirements horses have when they are under the stress of hard work, illness, or travel. It is designed to support normal metabolism, health, performance, and recovery. The composition, therefore, is not a problem for horses racing or competing in equestrian sports.

The route of administration can be an issue in some racing jurisdictions. In many countries, Pro-Dosa BOOST can be applied on the tongue, directly from the tube. In some, NOTHING can be administered on the day of racing; not even water. In those places, horses can often be provided with Pro-Dosa BOOST mixed in their feed. It is in a molasses gel, so most horses will eat it happily enough when offered in that manner. In others, it can be fed on the feed on race day, but only if it is normally fed between races as well. Please check your administration rules before deciding how to incorporate Pro-Dosa BOOST into your management system.

If you can’t even feed it on race day, Pro-Dosa BOOST can still be useful in managing your horses.

- Use Pro-Dosa BOOST to support recovery from work prior to racing.

Give a half or a full tube of Pro-Dosa BOOST immediately after the last fast-work prior to racing. You can adjust the quantity depending on how hard the horse has worked, the needs of the individual horse, the climate, and how far they will travel, or how challenging race day will be.

Good horses and problem horses will usually benefit from a full tube. Horses that do well, no matter what you do with them, will mostly be fine with a half. If you aren’t allowed to feed Pro-Dosa BOOST on race day, give the full tube post workout.

This portion will help to ensure that horses will recover more completely from their last fast-work before racing. Studies have shown that it can take up to four days for muscles to recover from hard work, and many horses will have their last fast-work session only a couple of days before racing.

Muscle cells take up amino acids much more efficiently for about an hour after hard work. If you can get a broad range of amino acids, in appropriate ratios for protein synthesis, into them during this narrow window of opportunity, you can make a difference to muscle cell recovery. Think of it like the protein shake a body builder would have after they finish a workout at the gym.

Of course, Pro-Dosa BOOST isn’t just amino acids. It also contains electrolytes, vitamins, and trace-minerals. Pro-Dosa BOOST contains the nutrients necessary to support normal appetite, nerve cell function, red blood cell production, muscle cell recovery, and electrolyte balance.

- Use Pro-Dosa BOOST to help horses in hard work to maintain normal appetite, body condition, and performance over a long season.

Give a half or full tube of Pro-Dosa BOOST immediately after each fast-work. Most trainers use Pro-Dosa BOOST this way in their horses. They believe they get more starts per preparation and more consistent performance throughout the season. For horses that struggle to maintain body condition during a long season, using Pro-Dosa BOOST this way can help to keep them eating normally, support muscle cell recovery, and help them to maintain muscle mass.

- Use Pro-Dosa BOOST to help horses recover from a race.

Give a half or full tube of Pro-Dosa BOOST immediately after returning home from a race.

While you may be outside the window for making the biggest difference to muscle cell recovery, you can still make a difference to how well your horse will eat, drink, replenish reserves, and recover.

Horses that have a hard run may not eat up well, and if they don’t eat, they won’t back up well. Pro-Dosa BOOST will support normal appetite and encourage them to clean up their feed when they get back home or to their stable. If you are allowed to feed them a syringe of BOOST prior to racing, they won’t need this dose afterwards. If you can’t feed them Pro-Dosa BOOST before racing, be sure to give this post-race dose when you get home.

- Use Pro-Dosa BOOST for travel.

Give a full syringe of Pro-Dosa BOOST prior to travel, and for longer journeys, give a syringe upon arrival.

We recommend Pro-Dosa BOOST for travel, especially when travelling over a long distance or over multiple days. Always have fresh water available and make regular water stops along the way. (Please consider any rules of competition that may apply before feeding Pro-Dosa BOOST as directed).

Providing your horse with one tube of Pro-Dosa BOOST, at least 2 – 4 hours prior to loading them on the float (or if you are leaving early in the morning, it can be given the night before, instead), will help them arrive at your destination in the best possible condition. If travel exceeds 8 hours, give another portion upon arrival, as long as that doesn’t contravene your rules of competition.

Using Pro-Dosa BOOST before travel will not only help protect muscles from oxidative muscle cell damage during travel, but it will also help support normal appetite. This can be especially important when horses are to be stabled away from home, in a new environment. This is ideal for horses traveling further afield and when racing in big campaigns.

- Use Pro-Dosa BOOST the day before racing.

From our cobalt clearance study, we found that Pro-Dosa BOOST had an impact on horses for around 18 hours; much longer than the 8-12 hours we had originally expected. If you are able to give a dose of Pro-Dosa BOOST the night before racing, you could reasonably expect the same results as you see when feeding it on race day. Please check the rules of competition that apply to you.

- Use Pro-Dosa BOOST as a health tonic.

Provide half a tube every other day to horses that may require more nutritional support when under the stress of illness.

Pro-Dosa BOOST has been widely regarded by the equine industry as a top-quality, nutritional aid for horses, given prior to competition, racing, or transport, after hard work for recovery, and at times of stress to support normal appetite, thirst, and health. What many industry participants are not aware of, however, is that Pro-Dosa BOOST can also be used effectively by stud managers and yearling preparers as a tool to help achieve top prices for yearlings as they go through the sale ring.

Yearlings, under stress during preparation, parades, transport, and at the sales venue, have significantly increased requirements for a number of nutrients including B-vitamins. Pro-Dosa BOOST contains all of the B vitamins in doses that are correctly balanced with each other as well as with all other nutrients. They are important for coat and skin condition, red blood cell and energy production (so tired or lethargic horses will get a lift), nerve cell function (so nervous horses will be better able to relax and focus), and most importantly, especially when yearlings have travelled to the sales and are being stabled in a new and stressful environment, they support normal appetite.

In the last two to three weeks leading up to the sales, it can be helpful to give half a tube of Pro-Dosa BOOST every other day, either mixed in with the feed or applied on the tongue. You will notice gleaming coats and the horses will eat and drink well.

While at the sales, try giving nervous horses one full tube of Pro-Dosa BOOST each day. It contains as much magnesium and thiamine as many calming products available on the market, and these nutrients actually work better when given in combination with each other and with the amino acids tryptophan and tyrosine than if administered separately.

For those that are not eating well or who are tired, give a full tube each day they are at the sales complex to support normal appetite and give them a lift.

Pro-Dosa BOOST contains 22 unassembled amino acids in good balance with each other. Unassembled amino acids stimulate thirst more effectively than electrolytes in dehydrated horses, and they provide the building blocks for protein and muscle cell growth.

Pro-Dosa BOOST contains a sizable dose of Vitamin C which supports normal immune function and scavenges free-radicals, thereby protecting muscle cells from oxidative damage that occurs in transport. They will arrive at the sales in the best possible condition if they are given a full tube a couple of hours before loading them to travel to the sales complex.

Always ensure horses have access to plenty of clean fresh water so they can keep hydrated throughout their preparation and sales.

Did you know that you are probably the very best person to determine if your horse is a “bit-off-colour”? You know “normal” behaviour for your own horse and you know their habits. Just by observing their day to day routine, you can get a feel for your horse’s general well-being and identify any changes that may indicate potential health issues. If you do become concerned about something, you will be better equipped to give the veterinarian a detailed account of when the horse was last normal and what has changed since then, to help in their assessment.

So what should you keep your eye on and what regular checks should you make to establish what is normal for your horse and then to monitor their health?

Here is a list of health checks that you should include:

Demeanour: Has your horse changed the way it acts? Horses should be alert and inquisitive, watching any changes in their environment. If your horse looks a bit sad, is uninterested in what is happening around them, and its head is down (and it is not eating or sleeping), your horse is off-colour and some further investigation is required. Contact your veterinarian.

Eyes: Your horse’s eyes should be open, clear and bright with no discharge or swelling. If you notice excessive discharge or weeping, swelling around the eye or in the corner of the eye, a closed or partially closed eyelid, sensitivity to light, or cloudiness, contact your veterinarian immediately. Eye problems are always an emergency and must be tended to urgently.

Appetite: Most people monitor how their horse is eating concentrate feed, but it is equally important to watch how much time is spent grazing in the paddock. Did you know that when turned out on pasture, a horse will graze about 18 hours a day? Keep an eye on your horse to see if it is spending more time grazing or standing around. If your horse is standing around more than grazing or leaving feed in its bin, then this should be investigated. Take your horse’s temperature and call your veterinarian immediately. Check their water, and look around the paddock or stall to see if they have been passing manure. The veterinarian will ask you about these things, as well as when your horse last had dentistry, and they will certainly do a more complete exam.

Water Consumption: Your horse needs access to clean, fresh water 24/7. A resting horse on a mild day can consume between 20 and 40 litres of water (five litres of water/100 kg of body weight). This amount can increase dramatically (up to 100 litres) after exercise, on hot days, or if lactating (broodmare feeding her foal milk). Horses also don’t like to drink water that is too cold, so if you live in cooler climates, make sure ice and snow is removed from water troughs and buckets. Some horses won’t drink as much if they graze on green, lush pastures as these will have a high-water content.

If you have difficulty getting your horse to drink, make sure the water is not too cold, is clean, and is fresh. If they are still not drinking that well, you can try offering an additional bucket of water with molasses or other tasty flavourings added to it to encourage drinking. Sometimes horses don’t like the smell or taste of plain water they are not used to. When you travel with your horse, if they are fussy about water, try bringing some from home, or if your horse enjoys a drink of molasses flavoured water at home, you can just bring some molasses with you to add to camouflage the taste and smell.)

Urine: Normal urine should be a pale yellow colour, a little like apple juice. If it is darker and thicker in consistency, it may be an indication of dehydration, kidney issues, or tying up. Due to the calcium content of equine urine, cloudy or foamy urine is also normal. Have you watched your horse urinating? Your horse should pass about 8-10 litres of urine per day and should urinate about every five hours. If your horse is having difficulty stretching out to urinate or stands unevenly while doing so, this could be an indication of lameness, muscle soreness, or kidney issues.

Manure: Have you checked your horse’s manure? If not, it might be time to take a closer look. Horse manure should be a rich medium brown colour and should be a formation of small round balls that shatter when they hit the ground. Your horse should pass manure six to eight times per day. In the spring, when pasture is more lush, the manure can have a green tinge and be quite soft. It can also be a bit loose at times of stress, after excessive electrolyte administration, or if there has been a change in diet. If soft manure continues for more than a few days, you should consult your veterinarian. Manure that is actually runny or is soaking the underside of the tail may indicate an urgent problem, so your veterinarian should be called immediately. If your horse’s manure is comprised of dry round balls that stay formed when they hit the ground, this can be an indication that the horse is suffering from dehydration.

Temperature: The normal body temperature of a horse should be between 37.0 and 38.5 degrees Celsius (98.6 and 101.3 Fahrenheit). Body temperature can be elevated because of inflammation and infection, but don’t forget, that a horse’s temperature can also increase when exercising, when rugged, in hot weather, and when they are excited. Body temperature fluctuates during the day, and it is often slightly higher later in the day. In mares, temperature can be seen to fluctuates with their heat cycle.

Body temperature should be taken rectally, ideally with a digital thermometer. (You can purchase a digital thermometer from your local pharmacy). If you have never taken a horse’s temperature before, get your veterinarian/instructor etc. to show you how.

Heart Rate: (Pulse) The resting heart rate of a healthy horse should be between 32-40 beats per minute (bpm). Draft horses will have a slightly lower normal rate, and foals will have a much higher one, up to 60-100bpm. Newborns will be towards the upper end of the scale, while older foals will have lower heart rates under normal conditions. Again, heart rate is affected by excitement, exercise, heat, pain, inflammation, and stress.

To take the heart rate, place a stethoscope on the chest just behind the elbow on the left side of the horse. Count the beats for a full minute, if you can, or for 30 seconds and then multiply by two to get the heart rate per minute. If you don’t have a stethoscope, don’t worry. You can take the pulse by putting your finger on the mandibular artery, found running your finger across the underside of the jaw, just where it joins the cheek or in the groove under the jaw inside the cheek, the radial artery on the inside of the knee, or the digital arteries at the back and bottom of the fetlock and along both sides of the pastern, at 4 and 8 0’clock. Be sure to use your fingers as you might feel the pulse in your own thumb.

Respiration Rate: (breathing) Watch your horse breathing over a full minute. When it inhales and then exhales, it has taken one breath. The normal respiratory rate for an adult horse at rest is 8 to 12 breaths per minute. In contrast, a new born foal will breathe 60-80 times a minute, and an older foal will take 20-40 breaths. As with a horse’s temperature, the respiratory rate will also increase with exercise, excitement, and in hot weather.

You can use a few different techniques to count the respiratory rate. The simplest way is to stand near your horse’s shoulder, facing towards its hindquarters, and watch its abdomen move in and out (one breath). As an alternative, you can feel for the air coming out of the nostril on your hand. If you have a stethoscope, the best way may be to listen to the breath sounds as air passes through the trachea (windpipe). This will enable you to hear the quality of the sounds your horse makes when breathing. You might notice deep or shallow breaths, and you might hear unusual crackling or whistling sounds that are an indication that you should consult your veterinarian.

Mucous Membranes: The mucous membrane are the tissues that line the gums, inside of the mouth, inside of the eyelid, inside of the nostrils, and the sac in the corner of the eye. They should be pink in colour and moist to touch. If the gums are dry or tacky, this can be an indication that the horse is dehydrated. Check the colour of your horse’s gums. If they are white, dark red, blue, or yellow-tinged, call your veterinarian immediately! These changes in colour indicate serious health issues.

Capillary Refill Time: This gives a good indication of how well the horse’s circulatory system is working. (A normal capillary refill time indicates that blood and oxygen is moving efficiently around the body). Push your finger on the gum for a few seconds until the gum in that area goes white, then release. The area should return to its original pink colour, within two seconds, as the blood returns to the area. If it takes longer than two seconds to return to normal, or if the gums are any colour but pink, call your veterinarian.

Skin Pinch Test (Skin Tent): This is another test to check your horse’s hydration status. On the neck, or on the upper eyelid if you are able, pinch a piece of skin between your thumb and forefinger for a second. When you release the skin, it should return to normal within one second. If it stays pinched for more than a second, there is the possibility of dehydration. The skin tent performed on the neck can be affected by age and body condition, with older animals and thin animals having a slower skin tent than younger and thinner animals. In horses, unlike in humans, the loose skin above the eye isn’t as affected by age, and fat doesn’t really accumulate under the eyelid.

Gut Sounds: You will generally need a stethoscope to listen to your horse’s gut sounds, though by simply pressing your ear to your horse’s flank in the right place, you will likely hear some. Place your stethoscope on the belly, just behind the ribs and in front of the stifle, on both sides. The second place to listen is a little further straight up from there, about the width of your hand in front of the whorl and about a hand’s width below it. Depending on the size of your horse, the specific location varies, so ask your veterinarian to help. You should be able to hear fluid rushing, tinkling, squeaking, gurlgling or rumbling in all four areas, but you will likely hear less in the top left area than in the others. You must be patient to hear gut sounds as they are not continuous. Listen for a full minute in all four places. Ideally, we expect to hear the sounds of gut contents moving a couple of times a minute. Researchers have found that eating or drinking results in more food particles and fluid passing through the digestive tract and an increase in gut sounds. If the rumbling continues at a much higher rate than normal, it may indicate some underlying issue and a veterinarian should be consulted. If gut sounds are very infrequent or not present at all, this can be cause for concern as there may be a blockage. Call your veterinarian immediately. In general, a slightly more active gut is not serious while a quiet gut will always require urgent veterinary care. Check your horse’s stall/paddock/stable for manure as this is a good indication of how long it has been since the gut was working normally.

Hoof Wall Temperature: An easy health check for your horse is to feel each hoof to see how hot it is. Hoof walls should generally be cool to touch, however each horse will be different. Get to know how warm your own horse’s hooves are in a variety of conditions. Exercise and warm weather can cause them to have an increase in temperature, so mildly warmer feet are not always a problem. It is especially useful to compare the temperature of the feet to each other. If one foot is warmer than the other, that is reasonably reliable indication of inflammation in the warm foot. It may indicate a bruise, the start of a hoof abscess, coffin joint synovitis, or a fracture. Tip: Watch to see if all four feet dry at a similar speed. Warmer feet will dry faster. If both feet are unusually hot for the conditions, it may be an indication of laminitis. A sudden flare up of laminitis is always an emergency, so call your veterinarian immediately!

Digital Pulse: Another indication of inflammation in the foot is a digital pulse. The digital pulse can be found on the back of the fetlock at the base of the sesamoids. By gently pressing and sliding your fingers side to side at the back and base of the fetlock, you can often feel the firm digital artery, which supplies blood to the extremities, roll under your finger. Once you locate it, lighten the pressure slightly to feel the pulse through it. You can also feel the digital arteries as they continue along the pastern at 4 and 8 o’clock, and only light pressure is required to feel the pulse here. If the pulsing or throbbing is quite strong and you can feel it easily, this may actually be an abnormal digital pulse and your veterinarian may need to do some further investigation. The normal digital pulse is a tricky one to locate, and this can be even more difficult on fit, healthy horses. If you get the opportunity, ask your veterinarian or instructor to show you how to locate it and try to get familiar with how mild that pulse is when it is normal.

My mentor in veterinary college, the great Dr. Otto Radostis, began all of our Large Animal Medicine lectures with a bit of his personal philosophy. This was one piece of wisdom he tried to impart on us that I will always remember. He said, “You miss more for not looking than for not knowing”. The best thing you can do is observe your horse in their environment, each and every day. Run your hands over them from top to toe, and get comfortable with doing the extra checks listed above. Keep a record of everything you see and of the daily health parameters you measure. Keep the information in your first aid kit (read our First Aid Kit blog article by clicking here) or stable so you have easy access to it. Remember, the sooner you notice that something is amiss and contract your veterinarian, the better the outcome is likely to be. Also, the more information you can give the veterinarian about normal and abnormal for your horse, the easier it will be for them to accurately assess your ailing equine friend.

“You miss more for not looking than for not knowing.” Dr. Otto Radostits

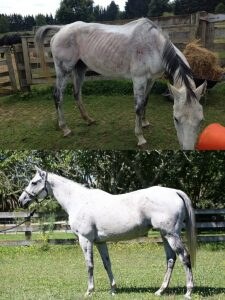

Below is a story from Michele of New Lives Animal Rescue based in the Waikato, NZ. This organization was established in 2014 and is a Registered Charity that specializes in the rescuing and re-homing of dogs, puppies, cats kittens, horses and can accommodate other species where possible. Pro-Dosa International Ltd. is proud to be able to provide support to New Lives Animal Rescue. To see how well these rehabilitation cases are progressing with the help of Pro-Dosa BOOST is really very cool!

“Thank you so much Pro-Dosa for your wonderful ongoing support of New Lives Rescue horses. We just love your BOOST paste!

All our rescue horses are given your paste on arrival, we find it is a great pick me up tonic and shows an immediate difference.

We thought it might be an appropriate time to tell you about how incorporating Pro-Dosa BOOST into your final stages of preparation could benefit your horse when training, travelling and racing. Pro-Dosa BOOST contains vitamins, minerals and amino acids in balanced proportions to replace those essential nutrients loss during exercise and when under stress.

Horses under stress (through hard work, travel and racing etc.) have increased requirements for a broad complex of nutrients necessary to support metabolism, health, performance, and recovery. Unfortunately, when horses are under stress, they tend to go off their feed, resulting in reduced intake of essential nutrients just at the time they need more.

Horses have significantly increased requirements for B-vitamins at these times, and Pro-Dosa BOOST contains all of them in doses that are properly balanced with each other and with all of the other nutrients required for their absorption and function. B group vitamins play an important role in coat and skin condition, energy production (so tired or lethargic horses may get a lift), nerve cell function (so nervous horses may be better able to relax and focus), and red blood cell production. Most importantly, when horses are transported and then tabled in a new environment, they help to maintain normal appetite!

Pro-Dosa BOOST contains a sizable dose of Vitamin C which supports immune function and helps to protect muscle cells from oxidative damage that occurs in transport and training. (Did you know that oxidative muscle cell damage can occur in as little as one hour, as the horse works to keep itself balanced during transportation)? Horses will arrive at their destination in the best possible condition if given one full tube of Pro-Dosa BOOST a couple of hours prior to loading them on the float each day. If you are leaving early in the morning, it can be given the night before instead.

If you have a nervous horse that does not settle into its new environment, try giving it half to one full tube of Pro-Dosa BOOST each day. It contains as much Magnesium and Thiamine as many calming products, and these nutrients actually work better when given in combination with each other and with the amino acids, Tryptophan and Tyrosine, than when administered separately.

Pro-Dosa BOOST contains a broad range of electrolytes including calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus, as well as sodium, potassium, and chloride. These will help maintain normal hydration and the electrolyte balance necessary for muscle cell, cardiac, and nerve function. Once horses are dehydrated, however, electrolytes will fail to stimulate thirst. When that occurs, unassembled amino acids stimulate thirst more effectively.

Pro-Dosa BOOST contains 22 unassembled, rapidly-absorbable amino acids in the optimal ratios required for protein synthesis and muscle development. Muscle cells take up amino acids most efficiently for about an hour following hard work. Providing a full tube of Pro-Dosa BOOST as quickly as possible after the last hit out prior to racing will aid muscle cell repair and recovery, ensuring horses will be in top condition on race day. A full or a half tube fed regularly after each fast work can help your horse to recover well, maintain normal body condition, and perform consistently over the long racing season ahead.

When race day comes around, give one full tube of Pro-Dosa BOOST on the tongue the night before or mix it in with feed.

We wish you the very best of luck over this fantastic racing carnival. if you require any further information. Contact the team at Pro-Dosa International.

Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome (EGUS) is a term that covers the damage and ulceration of the stomach lining in the horse. EGUS is a very prevalent disease affecting horses. EGUS is found in up to 90% of all race horses and endurance horses. The incidence of EGUS in sporthorses can also be as high as 60%.

The Stomach and Digestion Process.

The stomach is small relative to the size of the digestive tract of the horse and has a small role in the digestion process to help further liquefy food particles as they pass through to the small intestine.

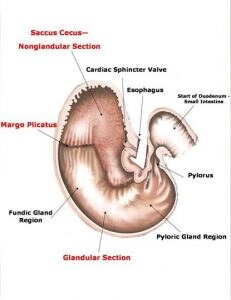

The stomach has two distinct areas the non-glandular section which is located the top one third of the stomach and has the same thin, smooth wall lining as the oesophagus. The glandular section of the stomach is the remaining two thirds of the stomach its wall lining is made up of glands which secrete hydrochloric acid, pepsin, bicarbonate and mucous.

The Equine Stomach showing the Glandular & Nonglandular Sections

Richards, Elenor – Equine Stomach, Nutrition for Maximum Performance

The horse is unique in that it continuously secretes hydrochloric acid to break down food particles. It also produces the enzyme pepsin that helps break down proteins. It is these gastric acids that ultimately damage the non-glandular region of the stomach as this area has thin, smooth walls which are not protected by glands as found in the glandular region of the stomach.

The time it takes for feeds to be digested in the stomach varies with the type of feed, forage or grain and the size of the meal. Grain can take as little as ten minutes to pass through the stomach and forage can take up to 24 hours so the stomach has little time to empty and hydrochloric acid is being used to break down food particles.

To address EGUS, our aim is to neutralise the stomach acid and the horse has its own neutralising agent bicarbonate which is produced in its saliva. As a horse chews it produces saliva the more time it chews the greater the amount of saliva thus bicarbonate produced. The bicarbonate then reacts with to neutralize the gastric acids.

It is important that all stable staff know the horses that are in their care so they are able to determine when there has been a change in their behaviour, eating habits, weight loss etc which could well mean the early detection of EGUS.

Clinical Signs of EGUS

The following are clinical signs that different studies have found can indicate EGUS.

- Horse cast or lying on its back

- Grinding its Teeth

- Poor Performance

- Weight Loss and Poor Body Condition

- Dull or poor coat

- Colic (Abdominal Pain)

- Changes in attitude and behaviour

- Poor Appetite

The only way to absolutely diagnose EGUS is by gastroscopy which is a long endoscope with a light and camera that is passed into the stomach via nostril and eosphogus to identify any ulcerations or damage to the stomach lining.

Management & Nutrition

- Provide high quality forage ad-lib, 1 kg of forage requires the horse to chew approximately 3000 times producing high quantities of saliva and bicarbonate to help neutralise gastric acid. Alfalfa high in protein 21% and calcium is ideal as there are buffering qualities provided by the calcium.

- Provide Water ad-lib at all times – water is required to produce saliva and studies show horses who are intermittently without water are more susceptible to ulcers.

- Keep horses on pasture 24/7 if at all feasible, as they are grazers and can do so for up to 18 hours per day and this will help keep feed passing through the stomach working to neutralize gastric acids.

- If horses are stall confined, make sure they can see other horses and can socialise to reduce stress. Give them a ball or something else to keep them amused and free from boredom.

- Feed smaller feeds more often, due to labour and time constraints many stables make the mistake of only feeding horses twice a day, which means the horse can go without feed for a period greater than six hours which studies suggest increases the likelihood of EGUS. Horses were designed to graze throughout the day not eat once or twice.

- Start with forage and build the diet from there adding a vitamin and mineral balancer then adding energy sources to meet requirements of the horse. Remember you can add fats such as oils to replace grain.

- If the horse bolts its feed place rocks in its feeder to try and slow its feeding rate down making it chew the feed, which means it takes more time for the feed to pass through the stomach.

- Transportation is a cause of EGUS – to help eliminate this break up longer travel periods to allow for rest, feed and water. Provide a travel companion to help alleviate stress.

- Performance horses are more susceptible to EGUS as they are often fasted prior to racing or competing, this needs to be addressed by the stable so the stomach does not completely empty out.

- Grains and or concentrates should never make up more than 1 – 2 kg of any meal given to the horse. Especially if it contains Sweetfeeds as these contain VFAs (volatile fatty acids) which can cause damage to the non-glandular stomach lining.

- Turning the horse out on pasture with access to quality forage for a period of a month will most likely allow the healing of any stomach ulcers, however this may not be practical for performance horses.

- The only registered treatment for the treatment of ulcers is Omeprozole (Gatroguard or Ulcerguard).

- There are other solutions available that line the stomach to help reduce the pain associated from ulcers.

If you require a PDF version of this fact sheet please click here and we will send one to you.

For more information read Dr Jenny Stewart “Update on Ulcers“

References

- Cubitt, Tanya. PhD,The Horse’s Digestive System,Hygain Health & Nutrition Articles

- Sykes, B.W., Hewetson, M., Hepburn, R.J., Luthersson, N. and Tamzali, Y. (2015), European College of Equine Internal Medicine Consensus Statement—Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome in Adult Horses. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 29: 1288–1299. doi: 10.1111/jvim.13578

- Andrews, Frank. M. DVM, MS, DACVIM,American Association of Equine Practitioners,Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome (16 June 20216),Website – Horse Health Publication 816

- Lesté-Lasserre, Christa. MA,TheHorse.com,Got Ulcers? (1 February 2014),Website – Article 33283

- Merck Veterinary Manual,Gastric Ulcers in Horses: Gastrointestinal Ulcers in Large Animals

- McClure, Scott. R, DVM, PhD, Diplomate ACVS, Diplomate ACVSMR, American Association of Equine Practitioners,Equine Gastric Ulcers: Special Care and Nutrition,Website – Horse Health Publication 817 (January, 2016)

- Geor, Ray. J. DVM, PhD.,American Association of Equine Practitioners,How Horses Digest Feed,Website – Horse Health Publication 861 (February, 2016)

- Liburt, Nettie. PhD, MS,TheHorse.com,Tips for Managing Gastric Ulcers in Performance Horses,Website – Articles 37542 (9 May 2016)

- Drs. Foster & Smith,Gastric Ulcers in Horses: Causes, Signs, and Treatments,Website – Article 1587

- Niteo, Jorge. DVM, PhD, DACVS,Centre for Equine Health, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis,Diagnosing and Treating Gastric Ulcers in Horses,CEH Horse Report (October 2012)

- Kentucky Equine Research,Gastric Ulcers in Horses – A widespread but Manageable Disease,Vetzone,Article (June 2012)

Upper respiratory infections are a significant problem across all equine industries and in the racing industry, in particular. Studies have demonstrated considerable economic losses resulting from subclinical disease (when horses don’t look obviously sick but are performing below expectations), from acute infection (when horses have nasal discharge, a cough, and obviously need rest or a reduction in training), and from the hypersensitivity and chronic inflammatory airway disease that develops in the lungs as a result.1, 2 As there has been a sudden increase in the number of upper respiratory infections in racing stables in New Zealand over recent months, I thought now might be a good time to write something about Equine Herpes Virus.

Most frequently, outbreaks coincide with yearling sales or a change in season, as this is the time of year in which racing stables introduce new horses to their yards, many of whom will bring “colds” or upper respiratory infections with them. Horses get “colds” just like people. They will have a fever, runny nose, sore throat, and occasionally a cough. Many will also appear depressed and lose their appetite.

There are a number of pathogens that cause upper respiratory infections in horses including Equine Herpes Virus, adenoviruses, rhinovirus, Equine Viral Arteritis (EVA), Streptococcus Equi Equi (Strangles), Streptococcus Equi Zooepidemicus, and Equine Influenza (EI). (In New Zealand, so far, we haven’t had EI…touch wood…) Equine Herpes Virus (EHV), identified over 60 years ago, remains the most common and economically significant cause of upper respiratory infections, world wide. 3,4, 5, 6, 7

There are actually nine different strains of Equine Herpes Virus, but only a few of them are clinically significant. The most important are EHV type 1 and EHV type 4 as they produce the most virulent, easily communicable, and most costly outbreaks across equine industries, all over the world. While EHV types 2 and 5 are ubiquitous (everywhere) and commonly cultured, the respiratory signs produced are generally mild, and they have not been demonstrated to produce serious outbreaks and economic loss. A recent study done in New Zealand determined that 44% of individuals from a small group with nasal discharge had positive cultures for EHV type 2 and type 5 was identified in 50%. EHV types 1 and 4 were only identified in 6% and 27%, respectively, though the small sample size and specific population tested were cited as limiting factors. Some heathy horses also cultured positive for EHV type 2 in the study, and the author explained that there were difficulties in positively identifying EHV type 4.8 All in all, the researcher found that EHV was strongly associated with respiratory disease. Previous studies done in New Zealand demonstrated evidence of recent EHV Types 1 or 4 infections in 72- 100% of horses and foals.9, 10

Equine Herpes Virus can be transmitted directly from horse to horse, but it can also be transmitted by droplets in the air (which can travel the length of a football field when a horse coughs). Exposure to virus particles in the environment on fences, gear, water troughs, clothing, shoes, etc. can also produce infection.

Horses of all ages are susceptible, but animals under three years of age and those under stress are most frequently affected. This would include most weanlings, yearlings, racehorses, and horses in training of any sort. 6

Immunity from natural infection lasts for only 2 to 6 months, so the same individual can become infected more than once in a year or their lifetime. While horses older than 5 years of age seldom show signs of illness, they often harbour the virus and provide a source of infection for the younger, more susceptible horses in the population. Young horses, with little immunity, will almost certainly become clinically ill when exposed. As they recover, over about 4-28 days, the virus, rather than being eradicated, enters the latent (silent) stage, sheltering in lymph nodes.6 Once the horse is under stress due to travel, training, or co-mingling at sales, the virus becomes reactivated and is shed into the environment, infecting other susceptible individuals. Studies have shown that between 60 and 88 percent of horses may be silent carriers.6

Other Clinical Syndromes Including Abortion and Neurological Disease

Equine Herpes Virus can cause a few different types of disease syndromes including respiratory disease, abortions, and neurological problems. EHV type 4 is believed to cause the vast majority (up to 90%) of significant upper respiratory infections11 and has been identified in some abortion cases, while EHV type 1 causes the majority of abortion cases, some respiratory infections, and most of the neurological cases.6

The evidence, so far, suggests that EHV infection begins in the respiratory tract, and once the virus multiplies enough in susceptible horses, it gets into their blood stream where it produces a “viremia”. (This just means virus in the blood.) If there is a large enough amount of virus in the blood, it gets into the central nervous system where it can damage the brain and spinal cord. It appears that EHV-1 is the only type, or at least, the type most likely to produce neurological symptoms as it appears to be the only one that settles in central nervous tissue.12

The neurological form of EHV (Equine Herpes Myeloencephalopahy or EHM) is fairly rare, especially in Australia and New Zealand, though there is some evidence that the incidence is increasing. 13

Clinical signs often develop 8 to 12 days after a respiratory infection and begin with weakness in the hind legs and incoordination. It can quickly progress, and within a day or two, horses will go down and be unable to get up. In some cases, no signs of respiratory infection are obvious, and the only early indication of a problem is a fever. Sudden weakness and death may be the first noticeable sign.

Alternatively, the viremia can allow the virus to get into the uterus. Once there, it causes the placenta to detach and the foal to be aborted. EHV-1 abortion was, up until the mid-80’s the most costly equine disease in North America, resulting in abortion storms that affected large percentages of mares on stud farms. From the mid-80’s, a widespread, aggressive vaccination program was instituted, and the incidence of EHV-1 abortion was reduced by 75%. Fortunately, in New Zealand, the incidence of abortion has been lower than in other countries.

Vaccinations

Treatment of viral infections is difficult. There are no really effective, economical anti-viral drugs available. Antibiotics do not kill viruses, and can only be used to treat animals with bacterial infections.

The best way to deal with EHV infection is to prevent it. Prevention requires a multi-faceted approach including quarantine, hygiene, and vaccination programs. Isolation of sick horses and quarantine of exposed animals and premises are useful measures, but they are not always practical at racing stables and farms. When horses attend sales or races, they are almost certain to be exposed to individuals who may not have been adequately isolated at their home stables and who may be shedding virus. Vaccination is the most practical way to reduce the rate and severity of infections in a racing stable environment where the horse population travels and changes regularly and in the racing industry as a whole.

Vaccinating a single horse will not reliably prevent that horse from getting sick if it is exposed to an overwhelming dose of virus.14 Instead, to protect individual horses from viral infection, it is necessary to produce “herd immunity”. The epidemiological term, herd immunity, can be explained like this. If 100 percent of the horses on a farm are vaccinated, it is expected that 70 percent of those horses will become immune. If 70 percent of the individuals in a population have immunity, then virus will not have enough susceptible hosts in which to multiply. This will reduce the overall viral load in the environment and reduce the viral challenge to each individual. This will stop the transmission of virus in the herd.14

That is the long way of saying that ALL of the horses on a farm or in a population must be vaccinated to prevent respiratory infection from being transmitted from horse to horse and therefore to protect individual horses.

A vaccinated horse may still get sick if it is exposed to an overwhelming viral challenge at the races or during shipping. They may be exposed to a sick horse or placed in a stall where a sick horse has been. Vaccination, however, will ensure that the horse will not get as sick and will recover faster than if not vaccinated. 15

Vaccinate all young horses frequently and older horses regularly, particularly if there is an outbreak. Use a modified live vaccine containing EHV 1 and 4, if possible. If horses have never been vaccinated for EHV before, 1 to 2 booster shots are recommended at 4-6 week intervals after the first dose. Foals should have their first dose at 4 months of age. Since immunity only lasts 12 weeks, one EHV 1+4 vaccine should be given every 3 months for optimal protection and for young horses in higher risk environments (racehorses in training would fall into this group), though the minimum recommendation is every 6 months.11,16,17

Vaccinate pregnant brood mares at 5, 7, and 9 months of gestation with an inactivated vaccine that contains only EHV-1, preferably at high antigenic levels. Pneumabort K, which is available in New Zealand, and Prodigy are two brands to consider.

There is very little evidence that vaccination can specifically prevent the neurological form of the disease, but recent studies have found that modified live vaccines can reduce the “viremia” and this may reduce the likelihood that the central nervous system of the horse will be affected.18

It has been noted that EHV types 1 and 4 are fairly consistent and antigenically stable,19 so unlike influenza viruses that mutate regularly, the same strains of EHV 1 and 4 remain basically unchanged over many years. The implication of this is that vaccines need not be adjusted annually or for each outbreak to be effective.

It is important to understand that once horses are affected with Equine Herpes Virus, they can continue to be carriers for life. At times of stress, they may begin to spread the virus around in their environment and infect susceptible horses around them. As a result, it is worthwhile to vaccinate young horses regularly to reduce the likelihood that they will become infected and then become silent carriers, even if there are no reports of a serious outbreak.

References

1. Viel, 2009. A New Understanding of Equine Inflammatory Airway Disease, OVMA Conference Proceedings, 2009.

2. Bailey, 1988. Wastage in the Australian Thoroughbred Industry)

3. Allen, GP, 2002. Epidemic Disease Caused by Equine Herpesvirus-1: Recommendations for Prevention and Control, Equine Veterinary Education, 2002.

4. Bryans, JT & Allen, GP. 1989. Herpes Viral Diseases of the Horse, Herpesvirus Diseases of Cattle, Horses and Pigs, edited by Wittman, G.

5. Crabb, BS. & Studdert, MJ, 1995. Equine 86 Herpesviruses 4 (Equine Rhinopneumonitis Virus and 1 Equine Abortion Virus, Advances in Virus Research, 45, 153–190.

6. Allen GP, JH Kydd, JD Slater and KC Smith. Equid Herpesvirus 1 and Equid herpesvirus 4 infections. Infectious Diseases of Livestock, (Ed.) JAW Coetzer and RC Tustin. Oxford Press (Cape Town), Chapter 76, pp 829-859, 2004.

7. Ostlund, EN, 1993. The Equine hHerpesviruses. Veterinary Clinics of North America, Equine Practice, 9, 283–294.

8. McBrearty, Thesis, 2011.

9. Dunowska, M, Wilks, R, Studdert, MJ, and Meers J, 2002. Equine Respiratory Viruses in Foals in New Zealand, NZVJ, 50, 140-147.

10. Dunowska, M, Wilks, R, Studdert, MJ, and Meers J, 2002. Viruses associated with outbreaks of equine respiratory disease in NZ, NZVJ, 50, 132-139.

11. Townsend, H and Morley, P, 1992. Western College of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Large Animal Internal Medicine, lecture notes.

12. Allen GP, JH Kydd, JD Slater and KC Smith. Equid Herpesvirus 1 and Equid herpesvirus 4 infections. Infectious Diseases of Livestock, (Ed.) JAW Coetzer and RC Tustin. Oxford Press (Cape Town), Chapter 76, pp 829-859, 2004. 13.

13. D.P. Lunn et al – EHV-1 Consensus Statement J Vet Intern Med 2009;23:450–461

14. Iverson, J, 1992. Western College of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Veterinary Epidemiology, Lecture Notes.

15. Patel, JR, Foldi J, Bateman H, Williams J, Didlick, S, Stark R. Equid Herpesvirus (EHV1) Live Vaccine Strain C147: Efficacy Against Respiratory Diseases Following EHV Types 1 and 4 Challenges. Veterinary Microbiology vol 92, Issues 1-2, 20 March 2003, pg 1-17.

16. Hines, M. Department of Veterinary Clinical Services, Washington State University, Recommended Vaccinations for Washington Horses, 2001.

17. AAEP website, 2001.

18. University of California Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, EHV-1 Vaccination Fact Sheet.

19. Allen, GP & Bryans, JT, 1986. Molecular Epizootiology, Pathogenesis, and Prophylaxis of Equine Herpesvirus-1 Infections. Progress in Veterinary Microbiology and Immunology, 2, 78–144.

20. Perkins, NR, Reid, SW, And Morris, RS, 2004. Profiling The New Zealand Thoroughbred Racing Industry, NZ Veterinary Journal 53, 69-76.